Gay Coding in Hitchcock Films

In typical Hitchcock-ian fashion, the "Master of Suspense" often employed in his films subtle references to gay culture, defying conservative attitudes of the late '50s.

Editor’s note: The following article, like many of Alfred Hitchcock’s films, includes references to sex and violence.

Did Martin Landau play a homosexual in North by Northwest? Did Alfred Hitchcock really show gay sex on-screen in Rope, albeit in an unusual way? Was the whole plot of Rebecca driven by the twisted jealousy of an evil lesbian? And, most surprisingly, did Hitchcock depict a gay marriage way back in 1938’s The Lady Vanishes?

The famed, late English film director Alfred Hitchcock was a complicated, twisted and mischievous man — characteristics that show up in all his great movies. He meticulously planned each film and knew exactly the effect each detail would have on his audiences. If he wanted to refer to homosexuality, as he did in at least 10 of his movies, Hitchcock would use what are now called “gay codes.” These are subtle references that gay people and their allies would recognize but could pass by most of the audience unnoticed. They are intentionally ambiguous in order to maintain deniability if questioned, especially by the censors.

Hitchcock was exposed to vibrant gay communities in both England and Hollywood, and he worked with many gay and bisexual professionals in various aspects of film production, including writers and actors. He knew their subculture well, and the gay codes in his movies were not an accident or an oversight. They were intentional, and he knew exactly what they implied.

The director was not prejudiced against gay people but instead fascinated by them. Hitchcock worked with too many of them to be anti-gay. In late 1920s England, Alfred and Alma Hitchcock socialized and were good friends with Ivor Novello and his partner, Robert “Bobbie” Andrews, who had lavish parties that were notoriously gay. Novello starred in two of Hitchcock’s silent movies and went on to a highly successful career writing musicals.

Hitchcock’s friendships and close professional relationships with gay people continued for his entire career. With his film Rope, screenplay writer Arthur Laurents and both young leads, John Dall and Farley Granger, were gay or bisexual, and Hitchcock knew it. He used Granger again in Strangers on a Train. Also, Anthony Perkins, who played Norman Bates in Psycho, was a conflicted homosexual or perhaps a bisexual.

Hitchcock intentionally used the stereotypes and misinformation of his era when they helped him manipulate the audience’s reaction, sometimes in highlighting the villainy of his villains. Society today is, in general, more accepting of LGBTQ people, making it hard to comprehend how toxic the societal attitudes were in Hitchcock’s time. His gay coding undoubtedly reinforced those toxic attitudes among straight audiences sometimes. However, Hitchcock’s thorough and thoughtful development of so many gay characters reveal his humanity and acceptance of homosexuality.

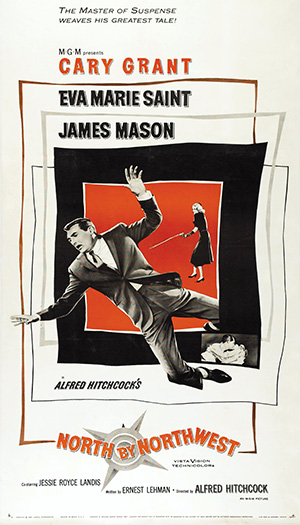

North by Northwest (1959)

The implied homosexuality in North by Northwest has only a few subtle but undeniable references. Leonard (Martin Landau) is the faithful henchman to Phillip Vandamm (James Mason), the communist spy being chased by the CIA. Leonard is a man interested in fashion, in the 1950s a cue for homosexuality. He is usually in the background; however, he comes to the fore toward the end of the movie in a masterful sequence set in a gorgeous mid-century modern house. Leonard shoots Vandamm, but with blanks, to prove that Vandamm’s girlfriend, Eve Kendall (Eva Marie Saint), is really a CIA operative. (We know, it’s complicated.)

Hitchcock filmed the scene from Roger Thornhill’s point of view, hiding outside on the balcony. Thornhill (Cary Grant) does not know there are blanks in the gun, and the audience doesn’t know either. Leonard is hiding the gun and getting into position to confront Vandamm. Why is Leonard all of a sudden shooting his boss? Hitchcock gives us the motive: homosexual jealousy. Leonard is secretly in love with Vandamm, who is abandoning him and flying off with Eve Kendall.

North by Northwest (1959) — Scene in the mid-century modern house toward the end of the movie.

Hitchcock sets up the possibility of Leonard’s homosexuality by giving him the line “Call it my woman’s intuition,” playing on a feminine stereotype. Then Hitchcock explicitly states the motive with Vandamm’s reply: “I think you’re jealous. I mean it, and I’m very touched. Very.” Vandamm is genuinely moved, totally accepting and even flattered — the exact opposite of homosexual panic. His reaction is a progressive perspective for its time but so brief that it doesn’t fully register with most viewers. Much later, Landau acknowledged that he played Leonard as a homosexual, albeit subtly.

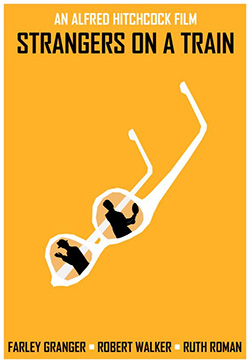

Strangers on a Train (1951)

The ambiguous nature of gay coding is well illustrated in Strangers on a Train. Many critics today read the character Bruno (Robert Walker) as gay. Hitchcock even cut different versions of the movie for Britain and the U.S., toning down the implied homosexuality in the American version — proof positive that he was fully aware of the gay implications in his movies. Some critics, however, simply leave out any mention of Bruno’s possible sexual orientation. They can, of course, because it is never explicitly stated.

Bruno is a sleazy character that entraps Guy Haines (Farley Granger) into a reciprocal murder scheme. Guy is a famous, well-connected tennis player. There are two scenes with gay coding and possibly a third. The first is at the beginning of the movie when they meet on the train. It can be read as a gay pick-up, or it could simply be a scene about a stalker with a plan. Hitchcock was aware of both possibilities.

Strangers on a Train (1951) — Three scenes: the pick-up scene at the beginning, the scene with mother in the middle, and a very brief carousel scene at the end.

The second scene has Hitchcock’s strongest gay codes in the movie. Bruno is teasing his mother (the wonderful Marion Lorne), who is clueless and flustered. He is obviously a mama’s boy and is dressed in flamboyant clothes, both cues of homosexuality at the time. This scene is gay coding at its most fundamental, obvious to some viewers and opaque to others. Some critics have argued that a third coded scene, Bruno and Guy fighting on a marry-go-round at the end of the movie, represents gay sex or possibly gay rape. The tenuous connection: Two men are thrashing around horizontally. It could represent what Bruno really wanted all along, sex with Guy, or it could simply be the exciting fight that wraps up the movie.

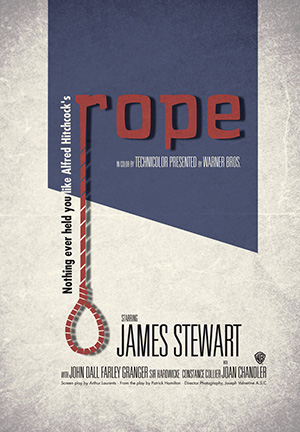

Rope (1948)

Rope is completely infused with homosexual subtexts, including one of the most amazing “sex scenes” in Hollywood history. After he had come out as gay later in life, Rope’s screenplay writer, Arthur Laurents, said in a DVD commentary of the film, “What was curious to me was that Rope was obviously about homosexuals. The word was never mentioned. Not by Hitch, not by anyone at Warners. It was referred to as ‘it.’ They were going to do a picture about ‘it,’ and the actors were ‘it.’”

The actors were definitely “it,” both as characters and in real life. Brandon (John Dall) and Philip (Farley Granger) are spoiled rich kids who murder a college classmate to prove their Nietzschean superiority. They are coded by Hitchcock as gay lovers. In real life, John Dall was gay but died in 1971 without talking openly about his homosexuality. Farley Granger was bisexual when making the movie and then was in a lifelong gay relationship starting in 1963. Alfred Hitchcock was well aware of the sexual orientations of both actors and was reportedly pleased with what is now called the on-screen “chemistry” between the two.

Hitchcock avoided obvious gay stereotypes in his portrayals of Brandon and Philip. Also, he could have easily incorporated indications that they were straight. Other directors regularly “straightened out” characters that were gay in the source material. He chose neither option for Brandon and Philip, keeping their homosexual relationship as just another, rather minor, aspect of their twisted personalities. As we will see, he did straighten out one other main character, however.

Rope (1948) — Murder/sex at the beginning of the movie and reliving it a few minutes later.

Rope’s plot traces back to the real-life Leopold and Loeb murder case in Chicago in 1924. Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb were extremely rich, talented academically and infused with a Nietzschean “superman” philosophy. To prove their superiority, they attempted a perfect crime, a thrill killing. They bungled it badly, murdering a 14-year-old boy, proving only their stupidity and pathological immaturity. They were easily caught. A letter was found from Leopold stating that he and Loeb had had a homosexual affair. During the trial, it was entered as evidence by the prosecution, who called them “cowardly perverts” and tried to establish their relationship as a contributing motive. The trial, especially Clarence Darrow’s defense, made national news. Leopold and Loeb were famous homosexual lovers and murderers.

In 1929, a British stage play on the West End called Rope and Rope’s End on Broadway, were loosely based on the Leopold and Loeb case. Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope is very close to the British play except for name changes and relocation from London to New York City. The plot is nearly identical; however, the play explicitly establishes that the two main characters are in a homosexual relationship, and their former school teacher, Rupert, is also a homosexual who had affairs with both of them.

Jimmy Stewart was cast as Rupert in the movie to provide the necessary star power. However, he would not be credible as a homosexual because of his straight persona, and he was too well liked by the movie public. Hitchcock removed all indications of Rupert’s homosexuality. Even so, Stewart was dissatisfied by his performance, and many critics feel he was miscast.

Gay people, especially gay villains, usually meet bad ends in golden age movies. According to the censors, they should not exist at all.

Hitchcock’s primary purpose in Rope was to discredit the Nazi Master Race philosophy. World War II had ended only three years before, and most of the world was still recovering. The homosexual theme was not his central focus, but it fascinated him, and Hitchcock, being Hitchcock, decided to have fun with “it.”

And did he have fun! He coded Brandon and Philip as gay by their “sex scene.” It occurs at the very beginning of the movie, which is also the murder scene. Hitchcock is strongly equating murder with sex. The murder-sex occurs behind curtained windows. The death scream corresponds to the orgasm. Now visible, the murderers Brandon and Philip quickly put the body in a cabinet and go into a postcoital exhaustion. Philip doesn’t even want the light turned on. In an inspired touch, Hitchcock has Brandon light a cigarette, a standard Hollywood indicator for “we just had sex.”

What follows is truly inspired Hitchcock. Philip and Brandon essentially replay the murder-as-sex again. It starts when Brandon gets champagne from the refrigerator to celebrate. He babbles on about the murder’s perfect execution as Philip is consumed with doubts. Brandon handles the champagne bottle, positioned between them as they stand close together. He holds its neck, fiddling with its tip, but never gets the cork off. He stops to get the champagne glasses then fiddles more. Something phallic is going on. Finally, in a piece of thinly veiled symbolism, Philip takes the bottle and pops the cork. They pour the champagne, raise their glasses and drink a toast to their victim. Not all of Hitchcock’s gay characters received the same clever subtlety.

Psycho (1960)

Most people now realize that gay men are not all effeminate, are not all mama’s boys, do not all hate women and do not all cross-dress. And they certainly are not all serial killers. But in 1960, many audiences would have conflated some or all of these traits in their general characterizations of homosexuals. Hitchcock chose Anthony Perkins to play the role of Norman Bates as a soft-spoken, slightly effeminate, young man. He is also a deranged mama’s boy who killed women. It’s hard not to attribute the character’s sexuality to part of a larger dangerous pathology. Likewise, another Hitchcock character in another of his films, Rebecca, sees her villainy exacerbated by her homosexuality.

Psycho (1960) — Dinner scene in the Bates Motel parlor.

Rebecca (1940)

Rebecca, like most Gothic thrillers, has to have a creepy villain. Hitchcock’s villain is a lesbian. And she is creepy. She’s also a housekeeper in a big, ominous mansion called Manderlay. It even has a closed-off, forbidden room. And lots of secrets. The house is essentially another character in the movie.

In mainstream Hollywood movies of the era, coding for lesbians was less prevalent than for gay men. In the 1940s especially, lesbians were portrayed as dangerous and threatening, so the character of Mrs. Danvers (Judith Anderson) was designed to fit that description. Mrs. Danvers? A married woman as a lesbian? In Hitchcock’s time that would be a contradiction that allowed the director to deny she was gay, if needed. However, the codes are there, and Anderson’s portrayal indicates she’s in on the act. Mrs. Danvers is obsessed with her former mistress, Rebecca, the late wife of Laurence Olivier’s Maxim de Winter; she’s seen only as a painting. Danvers is so obsessed that she is trying to drive the second Mrs. de Winter (Joan Fontaine) to suicide. It’s an obsession that demands explanation, and Hitchcock provides one — sexual desire.

The key lesbian coding comes in the lingerie scene in Rebecca’s bedroom. Mrs. Danvers shows the second Mrs. de Winter (no first name given) around the room. She sensually rubs Rebecca’s fur coat on Mrs. de Winter’s cheek. She shows her Rebecca’s underwear and runs her hands through the sheer lingerie with a subtle smile on her face. She describes Rebecca taking a bath and getting dressed. She pretends to brush Mrs. de Winter’s hair, as she did Rebecca’s. Finally, they end up at Rebecca’s bed, where Mrs. Danvers shows the monogrammed pillow case she created for Rebecca, along with a see-through negligee!

Rebecca (1940) — Entire lingerie scene plus the end of the movie.

Mrs. Danvers does not want the object of her obsession replaced, even after Rebecca’s death. Her jealousy becomes fundamental to the movie’s plot. She would rather die than live without Rebecca.

Gay people, especially gay villains, usually meet bad ends in Golden Age movies. According to the censors, they should not exist at all, but if they do they must be punished. Like many movies with lesbian coding, the gay woman in Rebecca must die. Mrs. Danvers burns herself to death in the ruins of Manderlay. The last shot of the film is the monogrammed pillow case going up in flames.

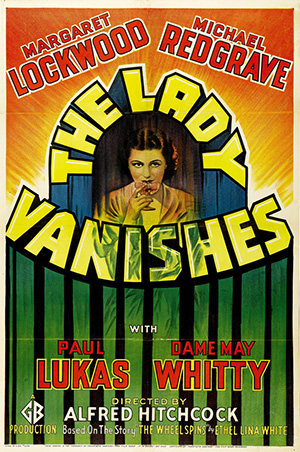

The Lady Vanishes (1938)

Almost all of Hitchcock’s references to gay people reflect the intense homophobia of the time. The characters Charters and Caldicott in The Lady Vanishes, however, provide one of moviedom’s earliest depictions of a positive gay couple.

Hitchcock excelled at getting fine performances from his supporting cast members. They usually are finely honed characterizations portrayed by perfectly cast actors, fascinating and funny, imbued with his dry British humor. Charters and Caldicott are wonderful examples. Played by Basil Radford and Naunton Wayne, two fine stage actors who reprised these characters in subsequent movies and BBC radio programs, Charters and Caldicott follow a long tradition of comedy duos of older men in British Music Hall, vaudeville and stage performances. Most audiences of the time, especially British audiences, would have interpreted their relationship simply as one between eccentric, middle-aged bachelors.

Charters and Caldicott are cricket-obsessed Englishmen trying to get back to London as they are entwined in a typically complicated Hitchcockian spy thriller. Hitchcock uses the characters to poke fun at his fellow countrymen, with much of their comedy coming from classic routines. The director also imbues in Charters and Caldicott a coded homosexuality. It revolves around a Germanic maid who speaks no English but is obviously interested in the two English gentlemen.

Charters and Caldicott are stranded at the only hotel in a tiny alpine village. The desk clerk tells them that they must share the maid’s room, but, she says, “I’ll remove the maid, of course.” When they first meet the maid, they respond to her “I’m interested” look with an expression that can only read “definitely not.” As they follow the maid to her room, Charters mentions off-handedly, “It’s a pity they couldn’t have given us one each.” Caldicott, thinking he meant “each a maid to have sex with,” is nonplussed. Charters quickly backtracks by saying he meant two rooms. All of this is very ambiguous. It can be read as Charters and Caldicott acting as proper, heterosexual English gentlemen. But there is a real aversion in their demeanor, even though the attractive maid is about their age and obviously interested. There is no doubt whatsoever that they are not attracted to her. Later, as they dress for dinner, the maid reappears. She wants to change and starts to undress. Her male roommates will have none of that and retreat so quickly that, in a minor comedic flourish, one of them mistakenly carries out a coat hanger.

The Lady Vanishes (1938) — The introduction to the maid scene near the beginning, the bed scene later that evening, and then multiple cuts from the ending of the movie.

The most persuasive gay coding, however, occurs in the bed scene. Set later that evening, it starts with a shot of the European edition of The New York Herald Tribune. We see only the newspaper being held by two hands, obviously by someone in bed reading it. We hear Charters complaining that the paper has only baseball reports and not cricket. The hands drop, and we see it is not just Charters but both Charters and Caldicott, squeezed together into the maid’s impossibly small bed. Caldicott has pajama tops on, but Charters is bare chested with only the matching pajama bottoms on. It is obvious they intend to sleep together that way. Do they have only one pair of pajamas and are sharing it? Definitely not, because clearly hanging on the wall are the matching top and bottom of a different set of pajamas.

The maid barges in without knocking but is not fazed by the couple in bed. The men lean away in avoidance. Caldicott places his arm across Charter’s chest in a protective manner and whistles through the episode. After the maid leaves, Caldicott jumps out of bed to lock the door. The unusually large pajama top extends to the middle of his thighs, and the shot is from the side, giving the definite impression that he is naked underneath. You can only just briefly see his boxer shorts as he turns when the maid barges back in again. This is undoubtedly beyond the behavior of two British gentlemen of the 1930s who are just friends.

Later in the movie, Charters and Caldicott become auxiliary heroes, handling danger with British calm and aplomb. They both join in a gunfight with fascists when their train is stranded, and Charters bravely assists the principle romantic hero, Gilbert Redman (Michael Redgrave), with restarting the train and escaping.

Charters and Caldicott are not sissy sidekicks, the most common gay male characterization allowed in American movies of the time (such as Edward Everett Horton’s roles in the Ginger Rodgers-Fred Astaire movies). They are not villains or minor characters, nor are their attributes confined to mere stereotypes. They are quirky but thoroughly capable and likeable, as much an example of honorable British manhood as the romantic hero. At the end of the movie, they are safe and together back in London, although the cricket match they so much wanted to see is rained out.

Charters and Caldicott are delightful as a gay couple. You could even interpret their relationship like a marriage — progressive, indeed.