Isaac Asimov: Writer, Polymath, Chemist, Mensan

Mensans recount the literary icon and former colleague 100 years after his birth

Isaac Asimov was one of the most prolific writers working in the English language, a world-renowned genius with deep knowledge in many fields. He was also an on-and-off member of Mensa starting in 1962 and Mensa International’s Honorary Vice President from 1974 to 1989.

Jan. 2, 2020, is the centennial of his birth. In honor of that milestone, we present these words on one of our organization’s most famous members.

* * *

Remembering the Literary Icon I Worked With

I discovered science fiction in elementary school and started by reading whatever was available at the library, so I know the first SF novel I read was something unmemorable.

In high school, I subscribed to the science fiction book club, picking books by size. Three-in-one, five-in-one, seven?! I was all over that. The authors? I had no idea. But that’s how I wound up reading Roger Zelazny’s Nine Princes in Amber series: seven complete books in two volumes! That’s also how I discovered Anne McCaffrey’s Dragonriders of Pern (at least, the first three, which were in that large, purple, three-in-one volume). It wasn’t until many years later, while I was working as an editor at Analog, that I discovered the first Pern book had actually first been serialized in Analog. And that’s how I came to have the big, thick, black-and-white-covered Foundation Trilogy by Isaac Asimov: because it was “three books in one volume, 800 pages.”

Sophomore year in high school, we lived in Buffalo, N.Y., and my mother, my sister, and I were taking the train to New York City for Passover with my grandparents. We got to the train at the last moment, scurried aboard with a week’s worth of luggage, and made our way to the only available seats in the car, which were those seats in the middle of the car, facing each other. I fell into my seat, breathed, looked up … and saw I was looking at my French teacher and his wife. Eight hours of looking at and talking with one of my teachers? That was not happening.

I buried my nose in the book I’d brought and read the entirety of Foundation on the train to New York. At first, I was avoiding an awkward situation. But it wasn’t long before I was hooked on the book. I read Foundation and Empire, the second book in the series, while we were in New York, and Second Foundation, the third, on the train on the way home (even though I wasn’t facing my French teacher).

In college, I read Isaac’s Murder at the ABA and realized that if I was ever going to be a writer, I wanted to be a writer who, like Isaac, could get away with writing himself into a book as the comic relief. That, instantly, became my definition of having made it as a writer.

Isaac took credit for writing (or putting together and writing introductions in anthologies and such) 477 books, which means I’m only about 471 books behind him. But because I spend most of my word creation time editing and publishing other people’s work, I doubt I’ll ever be able to match Isaac’s mark.

In college, I discovered that I am an editor and a writer. I worked at the student-owned daily newspaper and learned my trade.

I was also part of the student government and tried to set up a lecture series. Because I was at Boston University, I decided to aim high. I knew Isaac Asimov was a Boston University professor, so I wrote to him, asking him to speak in my new lecture series. He wrote back on a postcard, thanking me for the invitation but declining. That was my first direct contact with him.

After college, I moved to New York and got a job in publishing. It was the wrong job, and it wasn’t very long before my boss and I mutually agreed I needed to be working elsewhere.

I saw a three-line help wanted ad in the New York Times: “Wanted: editorial assistant for science fiction magazine. 380 Lexington Avenue, New York, NY 10016.” I said, “I know that address. I’ve been sending them stories. That’s either Analog or Asimov’s.” And I sent them a resume with a cover letter that basically said, “Gimme the job, gimme the job, gimme the job!”

Two interviews later, they gave me the job.

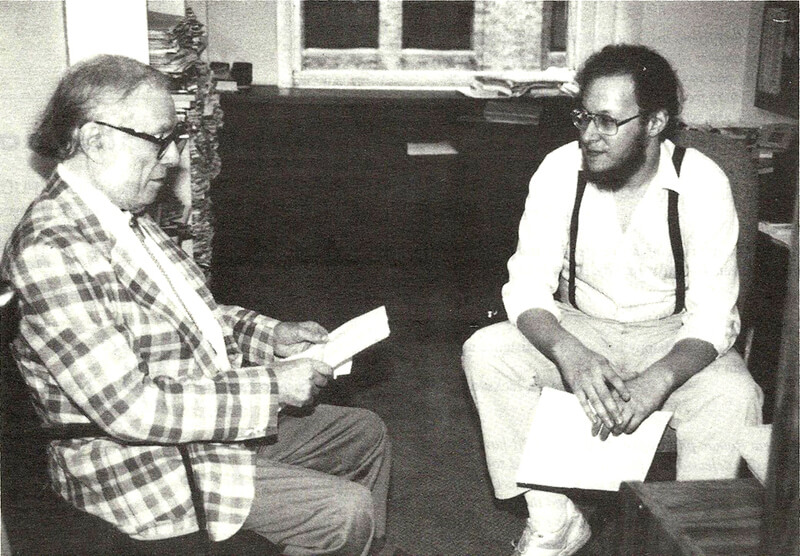

I started working on a cold Monday in the middle of January. My second day, Jan. 17, 1989, I was sitting in the office (the entire editorial department for both Analog and Asimov’s was one room, about 12 by 25 feet, with five desks, four filing cabinets, and a bunch of bookshelves) and heard singing coming down the hall. The door opened, and in walked a bundle of woolen winter clothes. As he took off a furry hat, a thick scarf, and a large gray coat, I saw a cheerful, gray-haired nebbish with glasses and heavy sideburns. Sure, I’d seen pictures before, but this was ISAAC ASIMOV, in the flesh.

After he settled in, my boss, Sheila Williams (now the editor of Asimov’s), introduced us. “Isaac, this is our new assistant, Ian.” He looked up at me; I looked down at him.

“You’re not a cute little girl,” he said. My two immediate predecessors had apparently been 5-foot-nothing and very attractive.

“You’re not a 10-foot-tall god,” I replied. I had to say something, after all.

“I’m not going to make up a limerick for you,” he said.

We laughed and were friends for the next three years.

Joel Davis was the publisher and owner of Davis Publications, which in the mid-1970s acquired Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine and Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. In 1980, he bought Analog. But in 1976, he decided to launch a science fiction magazine and approached Isaac about putting his name on the cover. Isaac was unwilling to edit the magazine but allowed his name to be used and took the title of editorial director (with the proviso that he would continue writing his regular science column in the now-competitor Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction). Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine (which was its original title; now it’s simply called Asimov’s Science Fiction) launched in late 1976, with Isaac writing each issue’s editorial and answering the letters to the editor.

The first three issues featured Isaac’s photo, very large, as the artwork. For the next eight issues, his photo was shrunken into the O in his last name, along with typical magazine cover art. Then his face was removed from the cover, except for occasional special appearances (for instance, November 1991, April 1992, and April 1993).

By the time I joined the magazine, Isaac’s routine was to come into the office for an hour or two every Tuesday. And the day I met him was no different (other than our introduction): He’d ask Sheila and Gardner Dozois, who at the time was the editor, if there was anything going on that he needed to know. They’d tell him everything was fine with the magazine and hand him the latest stack of letters to the editor (at the time, they came only on paper). He’d hand in his editorial every few weeks and a stack of letters with his answers. Then we’d spend the next hour or so chatting. I sat there almost mute — I was just a kid, and this was ISAAC — listening to him tell stories. It was wonderful!

Isaac was a great storyteller, a cheerful singer; he loved to tell jokes, and I hung on his every word.

Recently, I was talking with some friends about authors’ voices, how there are some authors whose voices I hear whenever I read something they’ve written. For instance, Robert J. Sawyer has a soft Canadian accent, almost unremarkable, but whenever I read one of his novels, I hear his voice narrating it. On the other hand, Allen Steele has a thick southern accent, but I don’t hear it at all when I read his books.

Isaac’s voice had a very thick, almost harsh Brooklyn accent. It sounded entirely natural as he sat there, every week, for three years. But so completely was it at odds with his written words that I’ve never heard it while reading what he wrote. And in the years after his death, every time I hear it recorded, I am at first shocked because it’s his written words I remember.

The last day Isaac came into the office was three years after I met him. By that time, we’d moved upstairs into a suite of offices. I was at my desk one Tuesday morning when the receptionist called to tell me Isaac was in the lobby and that I ought to come out.

Isaac always just walked back to the office, so that was the first sign something was amiss.

I got to the lobby and saw Isaac sunken into a chair, looking gray and uncomfortable, not breathing easily. I sat with him for a few minutes as he tried to catch his breath. Then Gardner came into the lobby. He, too, knew Isaac was in distress. He handed me some money and said, “Get a cab and take him home.”

We sat there a while longer until Isaac had recovered enough strength to stand up. But he was leaning heavily on my arm as we took the elevator down to the lobby and walked out to the curb. I hailed a cab, and he said, “Thank you.”

I said, “No. I’m taking you home.”

We got in the cab, and he gave the driver the address. Then he stopped talking, but he reached over and grabbed my hand, holding on for the entire ride.

We rode to his apartment in silence, and when we got there, again, he said he was good to go by himself. And again, I said, “No way. I’m going to make sure you get home okay.”

So we walked into his building, past the doorman, and up the elevator.

We stepped out on his floor, and then Janet, his wife, opened the door to their apartment. She said, “Thanks for bringing him home,” as she took him inside and shut the door. I stood there for a few minutes, at a loss. I wanted to do something more, but he was home. Eventually, I went back to the office, told Gardner he was home, and tried to get back to work.

That was the last time any of us in the office saw Isaac. Two months later, he died.

As we learned 10 years later — when Janet revealed it in her collection of his essays called It’s Been a Good Life — he had died of complications from AIDS, which he caught in 1983 when he had a blood transfusion during heart bypass surgery.

He was very weak and hospitalized for the last several weeks of his life. I imagine that must have been the hardest part of dying for him: that he was unable to write right up until the end. Well, that and the fact that he had more to write.

— Ian Randal Strock

* * *

Isaac Asimov: Mensa’s Natural Resource

Late in the last century, I was several times a speaker at the Dutch Treat Club, a group of New York writers and artists who met each Tuesday at Sardi’s restaurant. Those convivial gatherings were punctuated with laughter, music, and bright conversation. Each time I visited the Dutch Treaters, I watched Isaac Asimov, with his large, bright eyes; black-framed glasses; trademark silvery sideburns; twinkly smile; and clever wit, presiding over the festivities. Isaac and I would fire puns at each other, and one time he gave me his card. In its entirety it read:

ISAAC ASIMOV

NATURAL RESOURCE

From anyone else that would be a statement of vaulting pride and overreaching hubris, but not from Asimov. NATURAL RESOURCE is the natural label for the science fiction colossus who dreamt up the Foundation Trilogy, which he considered to be the most popular and successful of all his creations, and who formulated the three laws of robotics, bestowing upon robots the human touch through the I, Robot stories.

NATURAL RESOURCE is the natural sobriquet for one of the most prolific writers of all time and for the teacher we came to know in his innumerable guides to chemistry, biology, physics, astronomy, mathematics, genetics, geography, geology, ecology, prehistory to modern history, literature, Shakespeare, the Bible, mythology, Gilbert and Sullivan, the supernatural, and even jokes and limericks, both clean and funny. Making the mundane fascinating and the esoteric crystal clear, he might have been the world’s greatest explainer.

On April 6, 1992, Isaac Asimov shuffled off his mortal coil and journeyed to the undiscovered country from whose bourn no traveler returns. He had calculated that the average human being is allotted 2,830,000,000 heartbeats before expiration, and he himself had come very close to that number.

That’s all that was average about Isaac Asimov. He entered the earthly stage on Jan. 2, 1920, in Petrovichi, Russia, and his family came to the United States three years later. Isaac taught himself to read before he was 5, entered college at 15, and began writing professionally at 18. Typing away eight hours a day, seven days a week in his windowless writing room, he published and edited an average of 10 books each year, totaling more than 30 million words! When he wrote full time, he averaged 13 books annually. “I’m my own book-of-the-month club,” he crowed. A few other writers have birthed more books, but those products are almost always confined to a single genre, such as mysteries, westerns, and romances. They don’t come close to the scope and variety of Isaac Asimov’s multifoliate planets, which include nine of the 10 categories of the Dewey Decimal Classification System.

Fellow science fiction authors were in awe of Asimov. Frederik Pohl opined, “I’m sure there were another hundred books in that head.” Robert Heinlein added, “If Isaac doesn’t know the answer, don’t go look it up in the Encyclopedia Britannica, because they won’t know the answer either.”

To the rest of us, it would seem that anyone who fabricated more than 500 books, translated into more than 40 languages, must have reached an age of at least 250. But Isaac Asimov did all that by 72 and with fewer than 3 billion heartbeats. Barbara Walters once asked Asimov what he would do if the doctor told him he had only six months left to live. His reply: “Type faster!”

A life of such scriptomania would seem to require titanic dedication and discipline, but Asimov once confessed in an interview, “It seems to most people that to write my books I have to work, but it’s not work to me. The sensation I have when I write is pleasure. I enjoy writing, and there’s very little else I do enjoy. I have no self-discipline at all. If I had self-discipline, I could make myself turn away from the typewriter now and then, but I’m such a lazy slob I can never manage it.”

In another interview Asimov revealed that he wrote books because he found his more interesting than others on the same subjects. Given his quicksilver mind, unquenchable curiosity, voracious knowledge, flypaper memory, and reader-friendly style, his analysis was spot-on. By the end of his years, his ideas and vision had transformed our culture and collective imagination. What had once been confined within the tight boundaries of pulp magazines, such as Astounding Stories, now permeates how we live and move and have our being. In Isaac Asimov’s words, “We are now living in a science fictional world.”

— Richard Lederer