Add Wealth to Your Vocabulary

Language is the skin of living thought

DURING THE EARLY YEARS of space exploration, NASA scientist Wernher von Braun gave many speeches on the wonders and promises of rocketry and spaceflight. After one of his luncheon talks, von Braun found himself clinking cocktail glasses with an adoring woman from the audience.

“Dr. von Braun,” the woman gushed, “I just loved your speech, and I found it of absolutely infinitesimal value!” “Well then,” von Braun gulped, “I guess I’ll have to publish it posthumously.”

“Oh, yes,” the woman came right back. “And the sooner, the better!”

Now there was someone who needed to gain greater control over their vocabulary. But, realizing the power that words confer on our lives, don’t we all wish we could build a better vocabulary? If you enhance your word wealth, you will expand your thoughts and your feelings, your speaking and your reading and your writing — everything that makes up you.

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes once described individual words as “the skin of a living thought.” Holmes recognized that just as our skin bounds and encloses our body, so does our vocabulary bound and enclose our mental life.

Mark Twain’s novels and short stories speak to us across the centuries because they embody their author’s declaration “The difference between the right word and the almost right word is the difference between the lightning and the lightning bug.”

Suppose, for example, you wish to describe something of great size. You can haul out those two old standbys, big and large. But, if you possess an extensive vocabulary, you can press into service an army of more powerful and muscular adjectives: tremendous, immense, enormous, huge, vast, gigantic, or Brobdingnagian.

If, in addition to size, you wish to convey the suggestion of solidity and immovability, you can conscript words such as massive, bulky, unwieldy, jumbo, elephantine, and mountainous. If you want to create an image of clumsiness, you can press into service the likes of lumbering and ponderous. Hulking, looming, and monstrous add a sense of threat to the impression of size, while mighty, towering, and colossal indicate that the magnitude inspires awe. Humongous and ginormous are winkingly playful.

It’s a matter of simple mathematics: The more words you know, the more choices you can make. The more choices you can make, the more accurate, vivid, and versatile your speaking and writing will be.

I own the world’s worst thesaurus. Not only is it awful, it’s awful. Then somebody stole my thesaurus. To whoever did that, you made my day bad. I hope bad things happen to you. You’re a bad person. Now I have no words to describe how bad I feel.

Nonetheless, I love to collect thesaurus jokes:

What do you call a dinosaur with a large vocabulary? A thesaurus.

What does a thesaurus eat for breakfast? Synonym buns, just like the ones grammar used to bake.

I used to be poor. Then I bought a thesaurus. Now I’m impecunious.

I love using a thesaurus because a mind is a terrible thing to garbage.

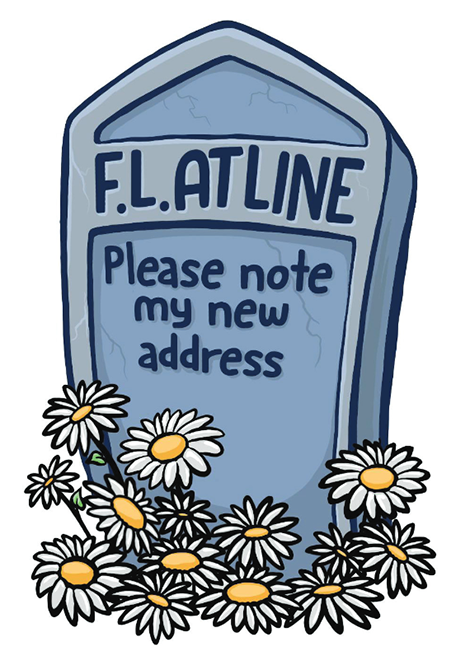

Speaking of synonyms, I regret to inform you that yesterday, a senior editor of Roget’s Thesaurus assumed room temperature, bit the dust, bought the farm, breathed his last, came to the end of the road, cashed in his chips, called it quits, checked out, cooled off, croaked, deep-sixed, departed this life, expired, finished out the row, flatlined, gave up the ghost, headed for the hearse, headed for the last roundup, kicked off, kicked the bucket, lay down one last time, lay with the lilies, left this mortal plane, met the Grim Reaper, met his maker, met Mr. Jordan, passed away, passed on, pegged out, perished, permanently changed his address, pulled the plug, pushed up daisies, rested in peace, rested under the sod, rang the knell, slipped his cable, shuffled off this mortal coil, sprouted wings, took a dirt nap, took the long count, traveled to kingdom come, turned up his toes; went kaput, west, the way of all flesh, and belly up, to glory, across the creek, to the happy hunting grounds, and to his final reward — and, of course, he died.

One of the best ways to grow your vocabulary is to dig down to the roots.

Words and people have a lot in common. Like people, words are born, grow up, get married, have children, and even die. And, like people, words come in families — big and beautiful families. A word family is a cluster of words that are related because they contain the same root. A root is a basic building block of language from which a variety of related words are formed. You can grow your vocabulary by recognizing the roots of an unfamiliar word and identifying the meanings of those roots.

For example, knowing that the roots scribe and script mean “write” will help you to deduce the meanings of a prolific clan of words, including ascribe, conscript, describe, inscribe, manuscript, nondescript, postscript, prescribe, proscribe, scribble, scripture, and transcribe. For another example, once you know that dic and dict are roots that mean “speak or say,” you possess a key that unlocks the meanings of dozens of related words, including abdicate, benediction, contradict, dedicate, dictator, Dictaphone, dictionary, dictum, edict, indicate, indict, interdict, jurisdiction, malediction, predict, syndicate, valedictorian, verdict, vindicate, and vindictive.

Suppose that you encounter the word antipathy in speech or writing. From words such as antiwar and antifreeze, you can infer that the root anti- means “against,” and from words such as sympathy and apathy that path is a root that means “feeling.” From such insights, it is but a short leap to deduce that antipathy means “feeling against something.” This process of rooting out illustrates the old saying “It’s hard by the yard but a cinch by the inch.”

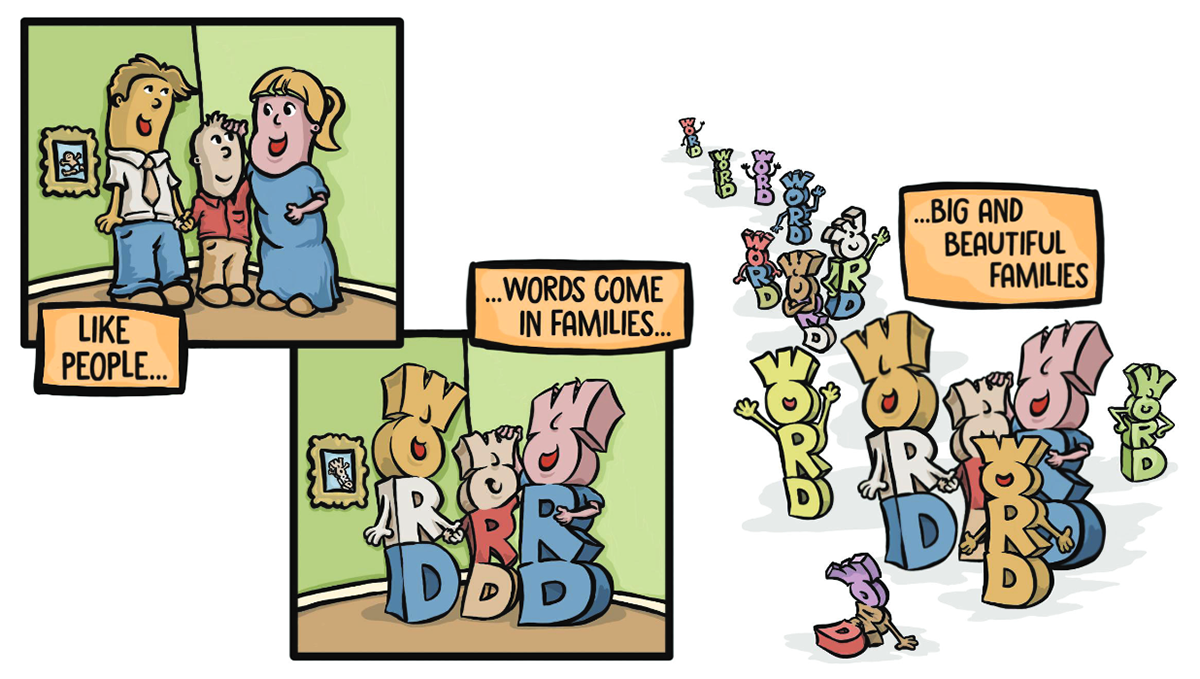

You can expand your verbal powers by learning to look an unfamiliar word squarely in the eye and asking, “What are the roots in the word, and what do they mean?” Here are 20 word parts descended from either Latin or Greek, each followed by three words containing each root. From the meanings of the clue words, deduce the meaning of each root, as in PHON - microphone, phonics, telephone = sound.

1. AUTO - autobiography, autograph, automaton =

2. CHRON - chronic, chronology, synchronize =

3. CULP - culpable, culprit, exculpate =

4. EU - eugenics, eulogy, euphemism =

5. GREG - congregation, gregarious, segregate =

6. LOQU - eloquent, loquacious, soliloquy =

7. MAGN - magnanimous, magnify, magnitude =

8. NOV - innovation, novelty, renovate =

9. OMNI - omnipotent, omniscient, omnivorous =

10. PHIL - bibliophile, philanthropy, philology =

11. SOL - isolate, soliloquy, solitary =

12. SOPH - philosopher, sophistication, sophomore =

13. TELE - telegraph, telephone, television =

14. TEN - tenacious, tenure, untenable =

15. TRACT - extract, intractable, tractor =

16. VAC - evacuate, vacation, vacuum =

17. VERT - convert, introvert, vertigo =

18. VIV - survivor, vivacious, vivid =

19. VOC - invoke, vocal, vociferous =

20. VOL - malevolent, volition, voluntary =