Mensan’s Elam Ending to Close NBA All-Star Game Again

Along with tribute to Kobe, the league's exhibition of studs will end with nod to elegant b-ball solution

Editor’s Note: In 2018, the Bulletin published this article from member Nick Elam proposing a more exciting and equitable way to conclude basketball games. For more than a decade, Elam had been developing a new set of rules assuring more dramatic final moments ending contests. Less than two years after the article was published, Elam’s new rules, dubbed the Elam Ending, were incorporated into the NBA All-Star game and earned rave reviews. The 2021 contest, set to be played March 7 in Atlanta, will also feature the Elam Ending, albeit with a small twist tributing the late NBA legend Kobe Bryant.

Basketball is a great sport that treats fans to some exciting, memorable final stretches. Basketball is also a great sport that tests fans with some excruciating, forgettable final stretches. What if basketball could keep or enhance all that we enjoy about late-game play and eliminate or alleviate all that we don’t? It might only require basketball to finally demote a once-indispensable element of the sport — the game clock.

The Problem

We’ve all seen it: crisp, competitive basketball games devolving into foul fests in the final minutes. Trailing teams repeatedly and deliberately foul their opponents as desperate means to stop the clock — the practice is bad enough on its face. Participants abjectly violate the spirit of the rules. It’s the type of fundamental glitch that would be unacceptable for any board game, card game, or video game, much less a major sport.

End-of-game fouling by trailing teams is worse still, given that it’s so unsightly, so unnatural, so unentertaining, so unfun. Worse yet, as counterproductive as the approach is — the trailing team essentially gives free points to its opponent — it still represents the trailing team’s best and only option. This makes the outcome of games too predictable and renders many proposed remedies unfeasible. For example, punishing the fouling team more harshly might seem reasonable, but this makes the trailing team’s only option even less appealing and could lead to even more fouling and fewer late comebacks than we already see.

Don’t take my word for it. The NBA, NCAA, and other basketball leagues and events have tried to address this very problem since the 1950s, and they continue to search for solutions today.

To be fair, basketball treats us to some great finishes, too. They’re what make me a diehard fan. But the sport, in its current state, is fragile. So many circumstances have to align just right for a game to feature a great finish along with good basketball in the possessions leading up to that great finish.

Blame basketball’s game clock. After all, it’s the ticking timer that forces teams to hoist hopeless shots at the buzzer, turning the game’s most important possession into blooper-reel fodder. And in the preceding possessions, the clock compels leading teams to stall and play passively. At the same time it compels trailing teams to foul deliberately, all the while making outcomes far too predictable. Many of the biggest and most competitive basketball games fade with a whimper and without even one signature moment or lasting image.

It raises the question: Does basketball really need a game clock? In a word, kinda.

The Solution

Basketball and the other sports employing game clocks (football, hockey, soccer, etc.) enjoy an important benefit by doing so: The clock helps rein in the length of games. So even though participants in time-based games to some extent manipulate the game clock, most of these sports must continue to rely on the timekeeper because scoring is sporadic, and the clock provides regular markers of interest. Now contrast, for example, relatively infrequent scoring in soccer and hockey with rapid point accumulation in tennis and volleyball, sports with so many mini accomplishments stacking up that no timer is necessary. Even baseball games regularly tick off outs. Points and outs essentially are the clocks for those sports. Basketball, meanwhile, features regular scoring and a clock. But it wasn’t always that way.

In basketball’s infancy, scoring was sporadic and precious, aligning the sport with others that truly are dependent on a clock. But for the many years since the game’s inception, basketball’s scoring rate has clearly distinguished it from other time-based sports, making basketball the only major sport that can have the best of both timed and untimed worlds. Basketball’s game clock isn’t misguided as much as it’s outdated.

In recent years, some basketball leagues and events (the American Basketball Association, The Basketball Tournament, and the NBA’s Summer League, for example) have effectively prevented the aforementioned late-game flaws, but only in overtime, by eliminating the game clock from that portion of the game. Instead of using a game clock for overtime, the teams play first to 10 points or first to 7 or even next point wins. That helps with overtime. But back in 2007 I saw possible merit in introducing this concept to not only overtime but also the final portion of regulation play.

My idea isn’t to fundamentally change basketball; in fact, it would do the opposite, preserving a more natural style of play through the end of every game and giving fans more real basketball during games’ late stages. The idea is for basketball to use a game clock for most of each game to reap its primary benefit, reducing the variability of game lengths; the game’s final portion, however, would be played without the timer, which would curtail unsightly strategies designed to manipulate the clock.

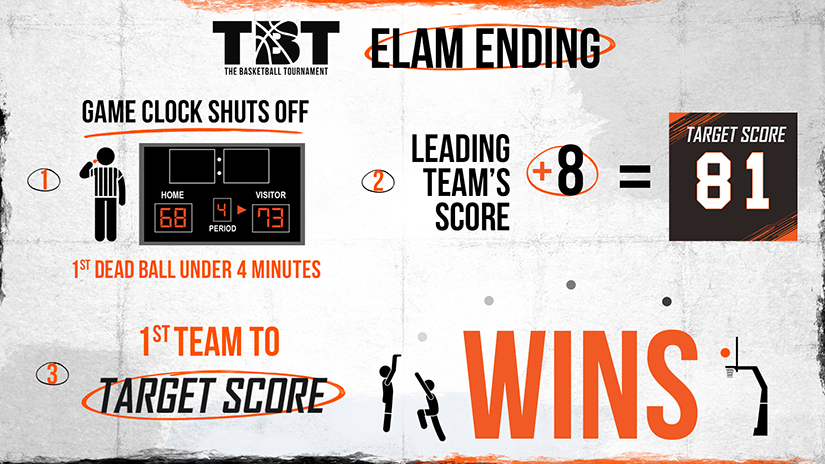

The settings of this hybrid duration format could be adjusted as necessary. One example would call for the clock to be shut off with four minutes remaining in the game and to play to a target score equal to the leading team’s score plus 7. Under this variation, if Team A leads Team B, 65–60, as the clock reaches 4:00, the clock is then shut off, and the first team to reach 72 points wins the game.

If sound, Team A wouldn’t play passively and couldn’t count on Team B to hand them free points by fouling. Team A would have to keep playing assertively to reach the target score. Team B would not have to resort to fouling or hoisting hopeless shots or throwing in the towel. And someone would seal their victory with the swish of a net.

The Implementation

Since 2007, I have researched the necessity of a hybrid duration format, gathering data about the clock’s warping effect on late-game play from a sample of thousands of NBA, NCAA, and Olympic games. Findings illuminate that in games where one team resorts to deliberate fouling, that team ultimately wins only about 1 percent of the time. Also, only about 1 percent of games end with a meaningful made basket — our beloved buzzer beater.

I have also investigated the hybrid duration format’s soundness, accounting theoretically for every possible unintended consequence or strategy that might be used to circumvent the format. Over the years, I have shared the concept and findings with a variety of stakeholders across the basketball realm; had the opportunity to write about the concept for Sports Illustrated’s The Cauldron and SportsDataResearch.com; delivered a guest lecture at the University of Cincinnati; and exhibited a research paper at the Basketball Analytics Summit.

In June 2017, the founders of The Basketball Tournament (or TBT, a $2-million, winner-take-all event broadcast on ESPN) renamed the format the Elam Ending and implemented it during preliminary round play. The format met all of its primary aims. Trailing defenses never resorted to deliberate fouling. Leading offenses stalled only minimally as the timed portion of some games wound down. And trailing offenses were able to maintain a high quality of play through the end of each game. Consequently, outcomes were less predictable. Trailing teams mounted crazy comebacks. Every game ended with the swish of a net, including some games that encountered heart-stopping next-point-wins scenarios. And the length of games varied only slightly from what they would have been with a clock.

Thank you @nba @TheNBPA @thetournament pic.twitter.com/3Pyemd3eiK

— Elam Ending (@ElamEnding) January 30, 2020

I attended all 11 games played over two days in Philadelphia and then watched the final portion of each game again after returning home, hearing for myself the positive feedback voiced on air by ESPN broadcasters Matt Martucci, Dave Resnick, Tim Scarborough, and Joe Lunardi:

“We saw a competitive game without delays or fouls all the way up until the end.”

“I’m on board. I like the way this Elam Ending helps the game and cleans up the game and creates more flow, which is what we like about our game.”

“Nick Elam isn’t showing much emotion, but he has to be thrilled at what he’s seeing.”

“I think the Elam Ending experiment was a very positive one. It was a lot of fun. I think the players really enjoyed it, and the fans enjoyed it as well. The drama is certainly there in this experiment.”

Leading up to and since the Elam Ending’s debut, I’ve had further opportunities to discuss the concept on various podcasts, including for Slate, NPR, KC SportsBeat, and Freakonomics; at the prestigious MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference; and at the upcoming International Conference for Sport & Society.

For 10 years, I’ve spoken on behalf of this concept, and now it’s finally had the chance to speak for itself. Better yet, now others in the basketball world are beginning to discuss, debate, and write about the concept more and more.

What started years ago as a search for a utilitarian solution produced something much better — an elegant and cool solution. What I once feared might be a gimmick appeared far less gimmicky in action than what we see now at the end of basketball games.

Organized basketball without a clock — for part of the game, anyway — just might be the way to make a great sport even greater. And after seeing the Elam Ending in action, I’m more confident than ever that the concept will live on, and I’m eager to see it grow, evolve, and be fine-tuned. The question isn’t if we’ll see the Elam Ending again, it’s when and where.