The Ancient Virtue Antidote

Can America's political split be fixed with Aristotelian inclinations to moderation?

Ruminating from within the world’s first democracy, Aristotle once wrote, “Those who think that all virtue is to be found in their own party principles push matters to extremes; they do not consider that disproportion destroys a state.” Two thousand three hundred years later, we might wonder whether the world’s most powerful democracy could be destroyed by those who disproportionately “push matters to extreme.”

Having exercised my civic duty to vote in 11 prior presidential elections, I am desensitized to the bombastic nature of political campaigns fat with ad hominem attacks and half-starved for meaningful discussion of issues — let alone practical solutions.

Standard fare has historically included charges of lying, flip-flopping, lacking qualifications, and beholding to special interest. Yet, somehow, those indignities now seem quaint. Adding to these red herring diversions, many candidates also feel they must demonize each other in the most slanderous or vulgar terms to appease a raucous base. It seems that populist anger on both the right and left is propelling a sort of American Spring. But instead of rebelling against a brutal government regime, we are revolting against long-held centrist pragmatism — that is, the sage view that dogmatic application of simplistic idealism will not sweep away our national problems.

A nuanced acknowledgment of the tradeoffs and ethical quagmires involved in virtually any proposal meant to address the big issues of the day is simply not enough for an angry mob. Naïve, morally corrupt, and/or hopelessly unworkable solutions are riotously cheered by unruly and sometimes violent audiences.

Would Aristotle blame this burgeoning lack of virtue on our incendiary politicians? Not entirely. We partisan citizens might whistle past history’s graveyard of failed societies by attempting to blame this darkness on the boogeymen of opposing parties conjured by their rivals. Accepting such claims is on par with believing that cheering Roman crowds had nothing to do with long-ago human slaughter in the Colosseum. Our politicians’ public personas mirror citizen values both right and left. As Aristotle put it, “… one citizen differs from another, but the salvation of the community is the common business of them all.” It seems we’ve forgotten the virtue of that common business.

Profiting on our amnesia, political activists and media pundits at the extremes of both sides pride themselves on having coached their respective bases into such an outspoken level of Manichaean zeal. Yet, closer reflection reveals an irony. Their uncompromising zeal has triggered fear, fertilizing the extremes on the opposing side. Hyperbolic mischaracterization has become the norm, and political activists have used it to poison much of what used to be considered the middle ground. Along the way, the U.S. has become more polarized.

Real Data

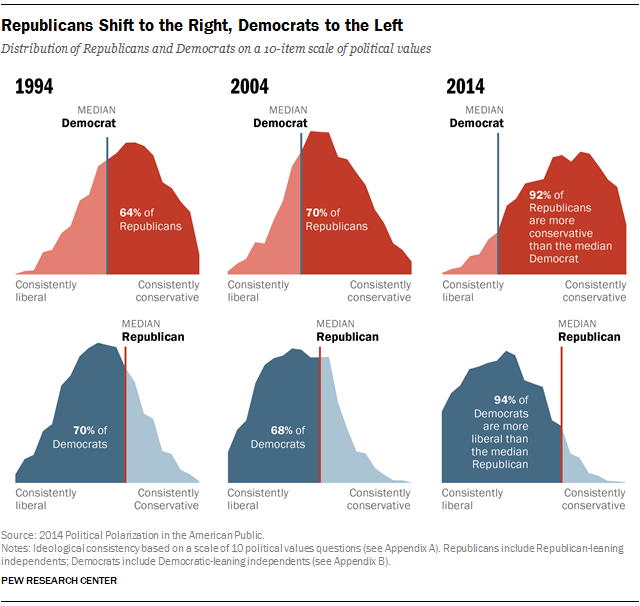

It might be tempting to think this polarization is a mere illusion created by campaign rhetoric reverberating in the media echo chamber; however, we have empirical evidence to the contrary. In June 2014, well before the 2016 election cycle, the Pew Research Center released results from one of its most ambitious surveys, Political Polarization in the American Public. That survey revealed, “… partisan antipathy is deeper and more extensive — than at any point in the last two decades.” According to the study, 92 percent of Republicans were more conservative than the median Democrat, and 94 percent of Democrats were more liberal than the median Republican. These figures are significant because 20 years prior, they were just 64 percent and 70 percent, respectively.

The traditional overlap between the views of the two main parties has withered. Even more worrisome, in 1994 only 16 percent of Democrats viewed the Republican Party as “very unfavorable,” and by 2014 that percentage had more than doubled to 38 percent. Republican views of the Democratic Party have deteriorated even more with 17 percent “very unfavorable” in 1994 growing to 43 percent by 2014. America’s polarization is real, and it has escalated to a mutual antipathy fanned into a nightly hysteria by shamelessly partisan “news” outlets on both the right and the left.

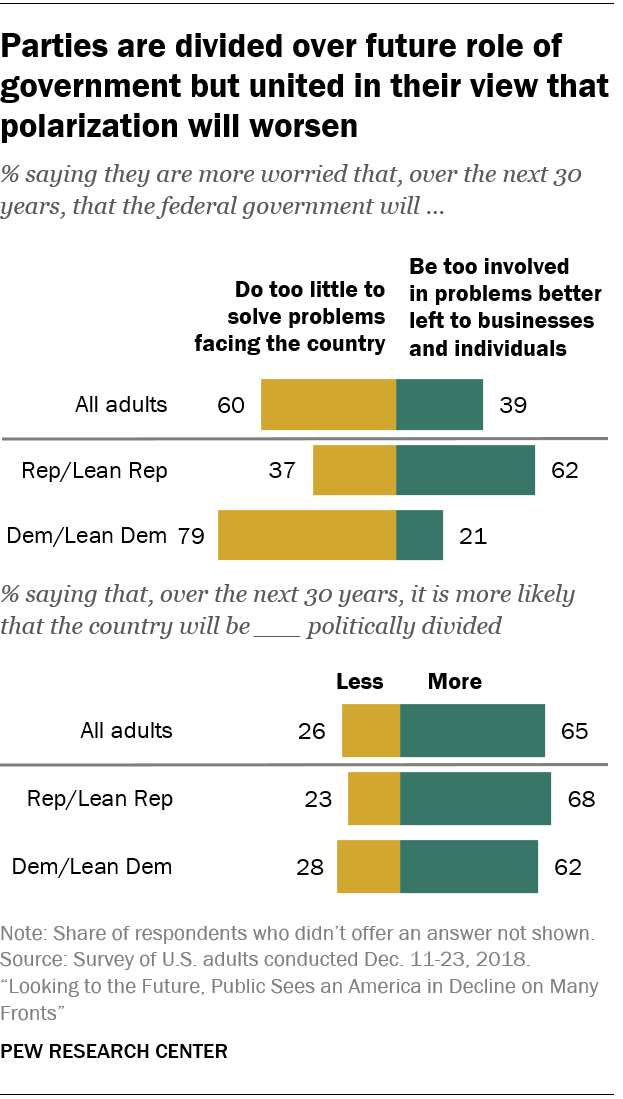

Reflecting on our own participation in this mutual antipathy, we might consider Aristotle’s admonition to practice moderation: “… anyone can get angry — that is easy … but to do this to the right person, to the right extent, at the right time, with the right aim, and in the right way, that is not for everyone, nor is it easy.” Such moderation seems a way off, given the 2019 Pew research showed 65 percent of respondents believe the U.S. public will be even more divided in 2050 — decades into the future! Who is to blame? How can we fix it?

A step in the right direction would be to reject altogether the question of who is to blame. The blaming of the other side is precisely what has fueled our polarization. Contemporary media programming reflects the growing acceptability of espousing unnuanced tribal dogmatism to stoke their target audience’s worst fears. Under the social pressure of growing political tribalism, ideological dogmatism has grown from a voguish display of political eccentricity on the part of talk show hosts to the widespread norm among regular citizens. Openly contradicting tribal norms risks not only being branded as a spineless infidel but also presumption that the offender covertly harbors the moral villainy of the other side.

This ad hominem worldview trap is ironic in that the genuine fears we are seeking to combat on both sides are grounded in wide areas of overlap when they are distilled into the nonpartisan language of our shared human condition, namely: fear of violence, fear of economic instability, fear of loss of liberty, fear of tyranny in the form of social or economic inequality, and, most recently, fear of disease. This irony represents hope. If we, Americans, can see ourselves as working on many of the same problems — or at least as harboring similar human desires to flourish — we might begin to overcome our mutual mistrust and heal division.

Here I suggest considering a tool largely forgotten or never known to the American public and having its origins in Aristotle’s Greece: virtue ethics. To explore how applying this ancient ethical theory might assuage current political dysfunction, we must first consider the practical use of ideology by the contemporary voting public.

Mass Ignorance

For the greater portion of the voting public, ideologies might be thought of as efficiency tools as opposed to comprehensive moral doctrines. In a 2008 article for Critical Review, “Is the Public Incompetent? Compared to Whom? About What?” political philosopher Gerald Gaus points out that, in a sense, it would be irrational for individual citizens to invest the resources necessary to be truly informed about issues and political candidates because the probability that their single vote will be decisive is nearly zero. As rational agents, our time is better spent securing access to things such as food, shelter, love, friendship, and family because the benefits of those pursuits more often exceed the costs of obtaining them. In contrast, the lottery-like odds of casting a truly decisive vote in any given election are barely worth the effort of voting. Your vote will, indeed, count. Nonetheless, its tiny contribution to the outcome is reason enough to channel your efforts toward satisfying life’s daily needs and spending little, if any, time researching political issues or candidates. This thinking has been referred to as the mass-ignorance hypothesis.

While most of us claim to be well informed when making political choices or espousing political opinions, we have already intuitively grasped the rationale behind the mass-ignorance hypothesis. As a practical matter, it is a challenge to dive deeply into the details surrounding candidates and issues without giving up time that could be used more beneficially for personal well-being. Shared principles and values expressed in political ideals often guide us to our decisions about candidates and issues without deep knowledge about them. Substituting ideology for information as a guide to political decision-making is a rationally justifiable way to use our limited time for political participation efficiently. However, a dogmatic application of ideology is harmful because it leads to troubling conclusions at the extremes while fueling the polarization America is experiencing.

Dogmatism’s Antidote

The antidote for ideological dogmatism and ensuing social divisiveness is the reintroduction of an ancient moderating ethical theory into our social and political discourse: virtue ethics. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy explains that, under Aristotle’s view, virtue ethics comprises three central concepts: virtue, practical/moral wisdom, and flourishing (arȇte, phronesis, and eudaimonia). The flourishing Aristotle wrote of is a kind of deep happiness coming only to those who have developed virtuous character through experience. Aristotle’s notion of virtue is notably different from our modern, folk sense of the word. The virtues are not just behavioral tendencies toward a fixed concept of some desirable personality trait. They are, instead, deep-seated, experienced-based modes of being that continually seek a well-reasoned mean between extremes, and that seeking requires practical wisdom. According to Aristotle, we are not born with practical wisdom. It is something we consciously cultivate through experience. It helps us find the actionable meaning of a particular virtue in a particular situation. Because of its role in developing virtuous character, we may think of practical wisdom as moral wisdom.

According to Aristotle, virtue is evidenced only in applying practical wisdom and rational thought to discover and act on the appropriate middle ground.

For example, what it means to be brave will vary with circumstance. To jump off a bridge on a dare when you don’t know the water depth below is rashness, not bravery. Yet to do that very same thing in an attempt to save a drowning child is brave. Therefore, bravery is a mean somewhere in between rashness and cowardliness. The virtue of being brave comes from having developed practical wisdom and exercising rational thought about what is worthy of risk and what you can reasonably expect to accomplish by taking that risk.

Generosity follows a similar rationale. To give large sums of money to a little-known charity without first investigating its reputation and use of contributions is not generous but wasteful. Yet, to give nothing to any of the many people in need when you have the financial wherewithal to do so is selfish. The virtue of being generous comes from having developed practical wisdom and exercising rational thought about what is worthy of your sacrifice and what is reasonable for you to forego.

I emphasize the word being in both examples because virtue is not simply about acting in Aristotle’s view. It is more deep-seated. The practical wisdom aspect is so internalized that it has become part of the person’s nature to find the well-reasoned mean between extremes. Virtue seeks the middle ground. In Aristotle’s own words (translated by W. D. Ross), “That moral virtue is a mean, then, and in what sense it is so, and that it is a mean between two vices, the one involving excess, the other deficiency, and that it is such because its character is to aim at what is intermediate in passions and in actions, has been sufficiently stated. Hence also it is no easy task to be good. For in everything it is no easy task to find the middle.” In other words, vice is a tendency to the extremes of either excess or deficiency, and virtue is evidenced only in applying practical wisdom and rational thought to discover and act on the appropriate middle ground.

Being virtuous in this way is not easy because it requires years of experience and conscious effort to develop practical/moral wisdom as well as the discipline to exercise rational thought rather than raw emotion before we speak or act. This sort of genuine virtue is visceral in that practical wisdom and rationality are not merely acted out but integrated into the person you have become. Their exercise brings happiness. This is, in part, Aristotle’s notion of flourishing. In this way, virtue ethics is about more than just actions and decisions. It is about what kind of person you are.

Applying Virtue

Though virtue ethics is an ideology in its own right, it need not supplant our political ideologies. It can instead operate alongside them. Because its emphasis is on the agent’s character rather than maxims, rules, or traditions, virtue ethics can augment or even police political ideologies. This is important at the extremes. When the dogmatic application of our preferred political ideologies causes them to outrun their range of applicability, we need a mitigating way to guide our decisions.

In the context of U.S. political divisiveness, one might challenge the mitigating power of virtue ethics by observing that dogmatic extremism is only a portion of our problem. While it is true that extremism aggravates our political divisiveness, the persistence of that divisiveness is largely due to people with outlooks stopping short of the extreme. Therefore, even if dogmatic extremists can be brought to see that genuine virtue requires moral wisdom in the form of seeking a well-reasoned middle ground, the non-extreme bulk of society would remain divided.

This challenge is met by starting work at the middle of society rather than at intransigent extremes. Our goal is to swell the ranks of the virtuous middle, and we can do so by employing contemporary interpretations of Aristotle’s virtue ethics. In particular, I have in mind those of New Zealand moral philosopher Rosalind Hursthouse as she communicated them in a 1990 Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society article, “After Hume’s Justice.” According to Hursthouse, virtuous action requires reflective rational thought on the moral agency of others as well as ourselves. In the context of implementing just law, this consideration has been referred to as Hursthouse’s constraint. It roughly goes like this: Laws may not be implemented if they require some members of society to act wickedly or wrongly — by their own moral lights.

This constraint is highly significant because it gives theoretical primacy to individual virtue. It recognizes that virtuous individuals can apply the moral wisdom they have nurtured over a lifetime but still disagree with other virtuous individuals regarding proper action. The challenge in implementing such a constraint is amplified in diverse and open democratic societies that necessarily rely on value pluralism to facilitate liberty. Persons are morally wise and virtuous to varying degrees, and yet individuals, by and large, believe they act rightly. As best summarized by political philosopher Mark LeBar in The Cambridge Companion to Virtue Ethics, we must accept Hursthouse’s constraint if “what we seek is an ethical story about how individuals with little overlap in values can coexist peacefully.” The implication is “that others are owed justifications of the use of coercive force against them in terms they themselves accept, or at least cannot reject at the cost of reasonability.”

Applying the spirit of the constraint to our individual contemplations and discourses regarding political matters in a sincere effort to nurture our own virtue will move us toward alleviating political divisiveness. In practice, as we struggle to settle our most contentious political issues, virtue requires that we ask, does my proposed resolution obligate other reasonable people to perform acts that are wrong under the lights of the moral wisdom they have nurtured over their lifetime? If the answer is yes, then we must seek a well-reasoned mean between our position and theirs — this as opposed to obeying tribal calls to simply demonize the other. In this way, a virtue ethics outlook helps to quell our tendency to myopically insist on outcomes strictly complying with our own preferred ideology. Additionally, the consistent application of this virtue ethics approach will put ennobling pressure on those with whom we disagree to reciprocate and perhaps even model our virtuous approach in their interactions with us and others. Virtue ethics exercised in the spirit of Hursthouse’s constraint can seed cooperation and mitigate political divisiveness caused by the dogmatic application of competing ideologies.

Enlarging the Tent

There are, of course, non-virtuous — wicked — persons, those who care little about the moral consequences of their actions or those who feign moral character but have no intention of reaching virtuous consilience with their fellow citizens. The good news is those sorts are in the minority. We know this because our complex human societies would not last long if most people were wicked. Therefore, we can practice a virtue ethics approach to our social and political interactions with others knowing that most of the time we are dealing with a person who is genuinely interested in doing right. As virtuous agents, we can use our practical/moral wisdom to find a well-reasoned mean between the non-virtuous extremes of ignoring the moral objections of virtuous others and accepting the dogmatic claims of blatantly non-virtuous actors. We will, of course, not always agree as to the location of that well-reasoned mean. Still, the very exercise of searching will develop our virtuous character while enlarging the tent housing our fellow virtuous agents.

My goal is not to discourage the application of rough-hewn ideologic principles in our political reasoning. It is, instead, to draw attention to how our political ideologies can be harmful if applied dogmatically. Virtue ethics can serve as a mediating ideology operating in parallel to others. This parallel operation not only has the effect of guiding us away from extremism but also assuaging the divisiveness making us drift away from reciprocal respect for the moral agency of others. We can still rely on conservative, libertarian, or liberal ideologies to guide our political reasoning while we use virtue ethics to police those ideologies when their recommendations begin steering us to extremes.

Some might worry that embracing virtue ethics could derail commitment to their preferred ideology, thereby leading them to hold incoherent positions. They might wonder how one can be committed to preserving tradition or honoring liberty, or delivering the greatest good to the greatest number of people, and yet shirk that commitment in the name of virtuous compromise when the going gets tough. Isn’t that sort of inconsistent behavior the mark of a dishonorable person?

This worry is driven by a misunderstanding of honor. Principled ideology can be honorable only if it is subservient to a virtuous character. While it is true that honor derives, in part, from tenacious commitment to principles, practical wisdom in the prosecution of that commitment is the only way to realize the potential for virtue to be associated with honor. Here again, a mean applies. Tenacity is the virtuous mean residing somewhere in between dogmatism and pliability.

Virtuous use of ideology requires an openness to moderation, acknowledging the limits of ideology and of our own wisdom. If that moderation sometimes causes us to decide against a principle we would normally hold, the inconsistency is both excusable and honorable. It is a recognition of: the limitations of political ideals outside their range of applicability or in the face of incomplete information; our limited available time to participate in the political process; our respect for the moral worth of others who don’t share our ideology; and our own need to foster reciprocity of that respect.

As virtuous agents, we respect the moral agency of others stemming from our shared humanity. Putting aside the question of who has the greater practical/moral wisdom, we can instead focus on our mutual need for and expectation of reciprocity in terms of not being obligated by political fiat to violate or support the violation of the ethical principles we have acquired through the development of our own moral wisdom. This reciprocity requires that we seek to understand the moral reasons underpinning the values driving the political opinion of others. This seeking might sway us slightly or even largely from our view, and it might not sway us at all. Nonetheless, the seeking rewards us in that our moral wisdom increases while our inclination to demonize those others subsides. We flourish as individuals and, over time, as a society. A widespread move in that direction would be an American Spring worth having.