The Art of Mystery/The Mystery of Art

A mother-son duo plots a whodunit graphic novel and lands on the biggest stage in comics

"You're doing what?" asked my girlfriend as she put down her fork. Though it might be uncommon for a septuagenarian to set a lofty goal that raises the bar, Mary Ann and I often talked over lunch about how to find happiness, and it is never in the dessert menu. She knew I believed in a correlation between living up to one’s potential and happiness … but not just happiness … rather, what Aristotle called eudaimonia — “doing and living well,” the ultimate form of happiness and the ultimate goal in life — using brainpower and reason to realize potential.

To that end, it was a happy “Let’s do it” when Matthew, my graphic novelist son, suggested we cowrite a book. Because we follow Hulu’s Only Murders in the Building and he thought the alternative ending I imagined for season one was “genius,” and because I once penned a few murder mysteries — when I was but a quinquagenarian — we dusted them off to see if we had a seed for a book. I live at the St. Regis, one of only two co-ops in St. Louis, so we knew plenty of personalities were there to draw inspiration. Though I did not have the excitement of NYC, like Charles, Oliver, or Mabel, I did have an apartment building full of characters. And the architects of my 1908 building designed and named it after the St. Regis New York, so the vibes were there.

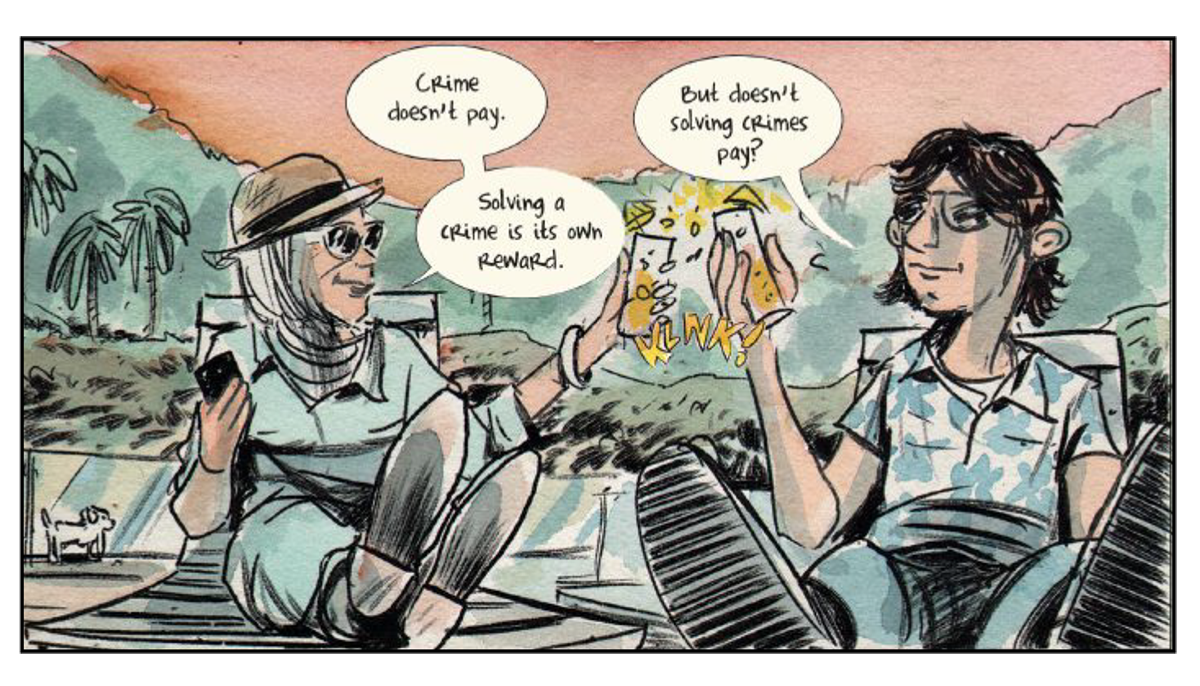

As soon as we turned the kitchen table in 7W into a partner table — Matt on one side and me on the other, with only our computers separating us — the fun began. We each took on the persona of our main characters: Merry, an adventurous collector with a knack for trouble, and Sam, her sharp-witted great-nephew. Merry and Sam threw dialogue back and forth, and we did the same, often laughing so hard at their exchanges that we had to stop and ask each other:

“Are you getting this down?” “No-o-o ... aren’t you?” After a few weeks, we had a draft of Gilt Frame, a graphic novel murder mystery that flits from Hawaii to St. Louis to Paris and finally Montenegro and fits the model of a three-act play. In part one, all hell breaks loose, and the unthinkable happens. In part two, everyone is set on either confuscating or cracking a grisly crime. By the end of part three, everyone knows where to point the finger — and do not dismiss the Maltese as a minor character; dogs are people, too.

There were few clashes. Matt and I have been a team since he was in utero. Plus, he had plenty of experiences with artistic collaborations, and I had the good judgment to defer to the pro … usually. My eyebrows lifted as I questioned Matt about some of the action that developed in our storyline: “Can we do that?” His comeback was, “I’ve done worse.” I thought the lead female character could have been drawn with a few more accessories, such as a scarf or bracelet, through a quick flick of the drawing pen, but as Matt pointed out, that detail gets lost when the image is shrunk to fit the book page. Well, OK.

If you live in St. Louis, all roads lead to the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, commonly known as the 1904 World’s Fair, so we decided to weave into the plot a real criminal, the woman in black, and her dumbfoundingly bold thefts from the Fair’s international exhibits of priceless treasures. When Matt insisted on keeping a panel where the woman was dressed in a low-cut evening gown rather than the obligatory daytime wear for a 1904 woman — he had already drawn it — the squabble ended with, “Do it your way, Matt, but it will be wrong.” When he responded with, “Then show me some examples,” I reminded him that in a large portfolio, I had hundreds of pictures printed from the original glass-plate negatives in the Fair’s photographic archive.

With fortuitous timing, while Matt and I were conceptualizing the broad strokes of the story, we won a pair of Louis XVI-style fauteuils through our local Selkirk auction house. With their intricately carved cornucopia arms spilling lush fruit, the gilt chairs slipped into the plot. Because of their known provenance, we suspected they were carved for the elaborate furnishings in the French Pavilion at the 1904 Fair — a replica of the Grand Trianon, the palace at Versailles. Charles Hooreman, the renowned Paris-based authority on French antiquities, told us that the fauteuils were carved around 1900, after a model by Georges Jacob — master carver for Louis XVI — with the original model today at Versailles. According to Monsieur Hooreman, we grossly overbid on the chairs. We humbly disagree.

While Matt drew hundreds of panels for Gilt Frame, bringing our imagined characters and their sometimes nefarious deeds to life, it was impossible not to develop a newfound respect for graphic artists.

Camille Pissarro, the 19th-century French Impressionist painter, moved his easel from one location to another when painting en plein air, searching for the perfect landscape to capture in oil. Inside his apartment, he moved the easel from one window to another, looking for the right scene to paint. Unlike Pissarro, who painted what he saw, a graphic artist must construct every detail from imagination. The terrain does not exist in this world until stylus meets iPad.

Though the 17th-century artist Rembrandt van Rijn is unparalleled as a portraitist, when he painted The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, each figure holds one expression. Not only the shaded face of the corpse but the visages of the spectators at the anatomy lesson are all frozen in time. The graphic artist, however, sketches a character’s face and then alters it hundreds of times, each variation manipulating the angle and changing the expressions, depicting a plethora of emotions that make the sparsity of words in a graphic novel OK because the image reveals what a character thinks and feels. “Show, don’t tell” is literal — the picture may not be worth a thousand words, but it replaces quite a few.

In Georges Seurat’s 1884 painting, A Sunday on La Grande Jatte, the French Post-Impressionist employs an artistic technique called pointillism. In this art form, the eye picks up individual, disconnected dots while the brain pulls them together and blends them, creating unity in a tableau. In much the same way, a graphic novel works as the reader’s eye registers each individual panel, while the brain connects the “dots,” pulling them together to make a blended, smooth transition in the movement and action of each character or figure as it moves across the pages.

When it was time to add color to hundreds of black-and-white panels, it took three generations to get the job done by deadline — mother, son, and granddaughter, Ella. Because Matt favored the way the pigment flowed onto the paper and how it looked when layered, one color over another, we each used pans of A. Gallo, honey-based watercolors handmade in Assisi, Italy. Though we each worked at home — Ella in her apartment at the University of Minnesota — we coordinated the cube numbers so the colors matched.

Experiencing new and exciting events or interactions for the first time is its own kind of eudaimonia, and San Diego Comic-Con offered them in unanticipated abundance.

Dark Horse publishers decided to issue Gilt Frame as a series of three comic-book issues before coming out with a hardcover edition — and launch issue #1 at San Diego Comic-Con. California, here we come! The Gold Rush was over, but Gilt Frame was just getting started.

Matt has been going to San Diego Comic-Con for more than 20 years, so he was not super excited to go that year. However, our publicist, whose job it is to get the book out there and noticed, won Matt over, taking unfair advantage with, “But maybe your mom would like to go.” For decades, I enjoyed the gathering vicariously, watching newsclips, hoping to spot Matt among the unconventional convention cosplayers. His mom did indeed want to go — let’s do it!

When it was time to add color to hundreds of black-and-white panels, it took three generations to get the job done by deadline — mother, son, and granddaughter.

This would be my first airplane flight since the Covid lockdown — an unwelcome first-time experience. I had a newly acquired Known Traveler Number, which is supposed to expedite airport screening, but not if one has packed six cartons of premixed tuna lunches sealed in foil. It had been a while … one forgets.

Predictably, as I wound my way to the Dark Horse booth within the sprawling convention center, a visual overview affirmed that I was indeed the oldest person there. When the hour struck for our scheduled book signing, the rope barrier dropped, and the first fan in the queue approached and handed us his prepurchased issue to sign, Gilt Frame #1 — a variant cover exclusive to Comic-Con. We whipped out our gold signing pens and got to work.

Due to Matt’s name and drawing power, we were part of a panel. And his collaboration with Keanu Reeves on BRZRKR landed us in a golf cart convoy from Keanu’s hotel to the convention center, where we chilled with Keanu in the holding room until their joint panel. He is just as kind, thoughtful, and amusing as reputed … and gorgeous. This feels a lot like eudaimonia.

Back home ...

as I thumbed through the latest Mensa Bulletin, a photograph and article caught my eye — only now I learn that a group of Mensans formed a panel at SDCC?! How did I miss them in the schedule of events? My loss.

After reading Gilt Frame, our French publisher — who has worked with Matt for years — wrote, “J’adore, ta mère est aussi folle que toi.” Matt said that, loosely translated, it meant something like, “How nice that your mother has found happiness.”

Matt lied; I later found out that monsieur said, “I love it, your mother is as crazy as you.”